“You’re going to Zion? Okay, you guys have to experience Zion the way I first did. Don’t even go into the park, hike in through the “Narrows,” spend at least three days and call me when you get out.”

I was eavesdropping as Carl talked to his brother Stan. I whipped out my phone and Googled, “The Narrows Zion.” My gaze fell upon the words “Number Five on National Geographic’s Top 100 American Adventures,” and I was sold! This hike was our new priority.

The Narrows, I continued reading, was a spectacular sixteen mile stretch of canyon carved by the Virgin River. According to the National Park Service, it was a hike that was “not to be underestimated.” There was no maintained trail, the trail was the river, and it ran swift and cold. Up to sixty percent of the hike was in the actual river — walking, wading, or swimming. Flash floods, were common and could be deadly.

“Double bag your electronics, dry bags recommended,” read another warning.

This sounded deliciously entertaining.

What ensued was the typical flurry of spontaneous, unorganized planning that was typical of all our best adventures. The water was running at 44 CFS, and the weather was forecasted to be clear and warm for the foreseeable future. There couldn’t have been a more perfect time to do this hike.

Reservations, made weeks in advance, were highly recommended. But, we were literally at the park entrance before we had ever even heard of the Narrows, and so we entered the backcountry permit office with nothing but high hopes and sheepish smiles to ask what the odds were of getting a permit for the following day. The ranger laughed, then check the system. Bewildered, he informed us there had been a slew of cancellations, and nearly every site was empty!

Five minutes and ten dollars later, we were back in the parking lot with a permit, the phone numbers for the three shuttle companies that made drop-offs at the trailhead, and two shiny silver bags for carrying our “waste” out of the canyon with us!

“Shudder!” I thought as I made a mental note to turn off my digestion for the next two days.

The shuttles left at 6:30 and 9:30 am and cost thirty-five dollars per person for the one and a half hour ride from Springdale to the trailhead at Chamberlain’s Ranch. We booked the 6:30 and then promptly realized that meant getting out of bed entirely too early to hike in the cold, so we called back and switched to the 9:30.

We had roughly sixteen hours to figure out footwear, dry bags, backpacks and food! We made a mad dash to the nearest grocery store, rented some dry bags, and found a campsite were we could sprawl our gear out on the picnic table to pack.

When we woke up the following morning, there was frost on the ground, and we were happy we had made the switch to the later shuttle. Hiking through a river (or swimming) in frosty temperatures would have been unpleasant. The ride to Chamberlain’s found us in a shuttle with two couples and a solitary man. We would be the only group headed into the canyon that day.

John, our driver, played tour guide as we headed out of town. He left us at the trailhead with the following advice, “that is the Virgin River, stick with it, and you can’t get lost.”

Sounded simple enough.

The first two miles of the trail wound along an old dirt road that meandered through meadow and desert scrub; we passed the time chatting with the solitary hiker, Tom.

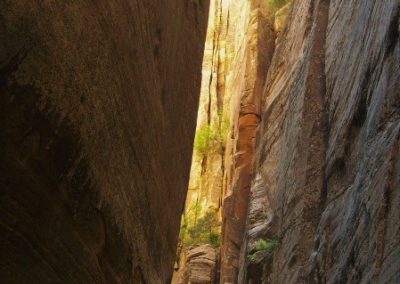

Almost as soon as we left the road, enormous orange canyon walls appeared before us and before long, we were completely enveloped in their magic.

I wouldn’t call The Narrows a hike, in the typical sense. It was more of a river wade, crossed with an amble, on a trail that was very much a ‘choose-your-own-adventure.” It certainly wasn’t a cardio workout or even that physical. It was however mentally tiring, as we had to be constantly aware of where we were placing our feet. It didn’t take long for me to be grateful for the ten dollar walking sticks we had hastily purchased at the grocery store.

The farther we walked, the more at home I began to feel. The canyon was silent, save for the melody of the water coursing over the rocks, leaping down waterfalls and disappearing around folds in the copper-colored rock.

The walls became tighter and higher with each step. In some places, if I held my walking stick outstretched in one hand and reached out with the other, I could touch both walls.

They rock was smooth and cool beneath my fingers, sculpted and carved by millennia after millennia of flowing water. I was ankle deep in something so ancient I could not begin to fathom it. Where the canyon widened, verdant life clung to the coral sand that had been pushed up against the canyon walls.

Walking by one such oasis of shimmering green, we startled a small bat. As he passed over my head, the soft light of early evening filtered through his nearly translucent wings and for a moment everything stopped. The entire universe melded, and there was nothing but the bat, and me, in a canyon so ancient its history has been forgotten a thousand times over. For a brief moment, we were all one, the bat, myself, the canyon, the water coursing underfoot and the soft light of a sun so far away I could not see it. An eternity in but a moment, and then I blinked, and the bat was gone, and I was left to continue walking in silent wonder.

At the confluence of Deep Creek, we stopped to filter water. It wasn’t long before our new friend Tom was back at our side. We could see campsite number one, so we knew we weren’t far from our own site.

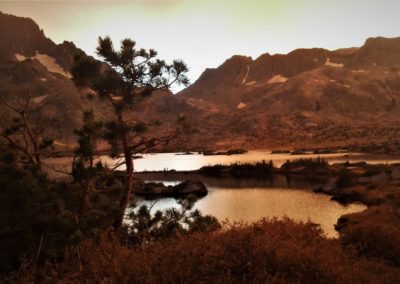

A quarter mile up the canyon, we found our campsite on a ledge of soft sand in a stand of small leafy trees. The site sat about ten feet above the river and was just big enough for us and our tent. It wasn’t much, but it was all we needed and then some.

My warm, dry camp socks felt like two giant hugs on my cold, pruned feet. We ate dinner, read and in the heavy silence we fell asleep almost before the last light had left the canyon floor.

The next morning I was awake early, making Choffee on a boulder the size of a van, and watching the sun slowly creep down the canyon wall. Peace and silence, as if the entire world had stopped.

We waited until mid-morning to start hiking, so the water wasn’t as cold.

It seemed impossible, and yet, as we walked the canyon walls got taller still until we had to crane our necks upwards just to see the rim. We passed towering waterfalls and lush, green living walls of moss, but no people. I felt so small, so insignificant, yet so safe. Like the Earth herself was cradling me in her loving arms.

With the added water from Deep Creek, most of our wading was nearly calf or knee deep, as we continued towards Zion and our exit out of this little slice of heaven. I never wanted this canyon to end; I wanted it to just keep on going, into forever. Unfortunately, nothing lasts forever. But then again, if it had lasted forever, would I have been able to appreciate it as much?

Just after noon, we rounded a corner and were hit with a cacophony of human voices. Laughing and shouting, reverberated off the canyon walls. The silence was broken. Day hikers jumped off of a large boulder and into the deep emerald waters of the Virgin. They watched, fascinated, as we skirted the boulder, waist-deep in water, trying to keep our packs dry. I don’t think it dawned on them at all that there was more canyon behind them to explore. I was happy to have them behind us until I realized that they were only the first wave of the Disneyland-ish crowds of National Park visitors we would pass through as we made our exit out of the canyon.

One last bend in the now crowded river and we found ourselves back in humanity, on a shuttle bus, the bat in the canyon now nothing more than a sweet memory.